(April 29, 2020) Introduction: Four years ago, when editor in chief Gail Picco was working on a book, she wrote a chapter featuring Chantelle Uribe, a young woman who spent three years as a street canvasser, or chugger as they are sometimes called. The profile never made it into the book, but we’ve updated it to give you a look into the lives of the people behind the clipboards.

You know them.

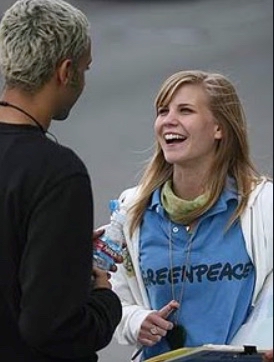

They do their work on the street and in pairs, eager young canvassers holding clipboards and wearing vests identifying them with the charity they are representing. They’ll see you coming a mile away, and when you see them, they say, can I talk to you for a minute? If you answer with a not now, they’ll wish you a very good day. If you stop by to chat, prepare to be engaged.

The sight of these fundraising teams has become so pervasive, in the U.K. they have become known as chuggers, a combination of charity and mugger.

Chantelle Uribe is 24 years old. She was a ‘chugger’ in Kitchener-Waterloo for three years.

Growing up in a large sprawling suburb of Toronto, Chantelle was surrounded by a mix of housing developments, industrial areas, factories and shopping malls. Chantelle’s mother has worked in customer service for a Mississauga company that makes salt for more than 20 years. Her father has worked in the syrup room of a soda pop factory close to Pearson International Airport. They are both very socially engaged. Chantelle has heard stories about them from other community members all her life.

“He’s the shop steward of the union local,” says Chantelle over coffee in a neighbourhood café on an overcast day in February. With a cotton scarf around her neck, she has wavy dark hair touching her shoulders, and brown eyes that are bright and lively.

“He’s all about power to the people and has a big Che Guevara tattoo on his arm,” she said of her father.

“When my dad looks at the greed in society, it leaves a very bitter taste in his mouth. He’s very much a ‘love your neighbour’ kind of guy. When he looks at systemic injustices, he gets frustrated. I’ve always tried to connect him to a cause he might care about but he says he just hates people,” Chantelle said with a big laugh.

Chantelle’s mom and dad came to Canada from Colombia in the 1970s. Her mom was eight and her father was 12. I ask, was it her parents that taught her about social injustice, and inspired her sense of charity?

“Oh no. I was born in the early 90s and I saw a lot of DRTV, you know, direct response television, for lots of different charities. I wasn’t their target audience, but I had the urge to respond. I pestered. Mom, Dad, can we donate, can we give? Can we give? Please? Please?’”

“They brushed me off with different excuses. You are our charity, they’d say. But, for me, that’s where my whole interest in charity started. Honestly, some of those ads really stuck with me. I didn’t know who some of those celebrities were at the time, but it hit home.”

Once Chantelle finished high school, she moved ninety kilometers west to Waterloo to begin her undergraduate degree in arts at Sir Wilfred Laurier University.

Street canvassing, also called face-to-face or direct dialogue fundraising was pioneered during the mid-1990s by Greenpeace in the U.K., an organization well-known for its attention-getting campaigns on a range of high-profile environmental issues from whaling to Arctic drilling.”

They were looking for new donors- especially younger donors, like Chantelle. And they wanted their street canvassers to reflect the people they considered prospective donors. So, they hired informed and articulate young people who were passionate about the environment, organized them into two-person teams (for safety, and to maximize their personal charisma), gave them clipboards and aprons clearly identifying them with Greenpeace, and sent them out on the street. Their job was to approach people and engage them in a talk about the environment. When the conversation progressed, they popped the question of becoming a monthly donor of Greenpeace.

By 1998, Greenpeace had acquired 300,000 new monthly supporters and rolled street canvassing across the world. Other charities, seeing Greenpeace’s unusual success with a younger demographic, started their own street canvassing campaigns. Throughout the next two decades, many more charities would embrace street canvassing as a fundraising tool.

When Chantelle and her roommate were trying to figure out summer plans, her friend suggested Chantelle join her at the company where she’d spent the previous summer doing street canvassing for a range of clients.

“Just think about it,” she said. “These kids who get sponsored, they have an opportunity to get an education all because you just had a conversation with someone on the street. How cool is that?’”

Remembering the DRTV she watched as a child- and knowing she loved to talk to people, Chantelle signed up. This is my calling now, she said.

It’s one thing to be an environmental activist that is out on the street seeking support for your cause. It’s a different matter to be a mercenary- to take on many clients, many caues, and be equally engaging for them all. Chantelle quicklylearned the value of a good, well-learned pitch.

“I fundraised for the CNIB, the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health and the Nature Conservancy of Canada,” she says. “The ones I did that were international were Plan, Médecins Sans Frontières, Amnesty International and UNICEF. They’re all so different.”

Here’s how she framed her approach to street canvassing for the CNIB:

“I was surprised by how many people whose lives were affected by extreme vision loss, whether it was someone they knew who had age-related macular degeneration or one of their old professors who had to have cataract surgery. And by how many people weren’t able to make those connections themselves.”

“Whether that was cooking, going for a run or even just reading, I’d say imagine if you lost your vision, would you still be able to do that? Most people think no, but those are things that are still possible. Most people think no, but after vision loss, people can still run marathons, read books, cook. It’s just a matter of having the resources available to you. Having those genuine conversations with people really builds a connection between them and the organization. To me, it was the most interesting part of CNIB.”

For Chantelle, going door-to-door for the Centre for Mental Health and Addiction (CAMH) was an opportunity to meet people who themselves or their family were dealing with mental illness in their own life.

“I felt so fortunate because those donors shared their personal stories with me and thanked me for getting out there and getting the conversation going because there’s such a huge stigma associated with it. People were grateful we were out there having those conversations.

“CAMH was actually around it the time I was going through a lot of anxiety about school and it made me realize that I too maybe needed to reach out for some help. It was really heavy, but it was so worth it and, looking back on it, it really changed the course of my life after that because, honestly, if I had continued on with that kind of anxiety that I was experiencing, I don’t know if I would have graduated from university.”

“Nature Conservancy was probably the toughest one,” she said.

“A lot of people don’t see an immediate urgency when it comes to fundraising for the environment or donating to the environment. Because you can tell someone, you know, the Amazon is disappearing at a rate we’ve never seen before, but unless you can actually visualize what that looks like, those kinds of numbers and statistics don’t always register.

“With Nature Conservancy, it was a very niche group of people. But the people who cared, really cared, and were very invested.”

After graduating with an arts degree from Wilfred Laurier, Chantelle decided to join the Fundraising & Volunteer Management Program at Humber College in Toronto.

“When you are working as a street canvasser, you are on a very small part of an annual campaign. At the time, I didn’t even know what an annual campaign was. All I knew was that this is an amazing organization and there’s a need for support.

“Now, I can see the bigger picture. I see what goes into planning an annual campaign as well as major gifts and legacy-giving.”

While at Humber, Chantelle volunteered in the planned giving department of the Arthritis Society of Canada, helping with legacy communications.

“It might not be the sexiest area,” she says, “but for me, I see legacy donors as so dedicated, loyal and passionate about their causes. When I became interested in pursuing this line of work, that special connection was really motivating for me … meeting folks who are so dedicated.”

When I asked what kind of organization she’d choose to work for, given the chance, she thinks those would be the ones that have to do with health or with the environment or the arts- but the environment especially.

“It might just be a product of my generation and seeing how real climate change is and how bad it’s getting. My family had a 40th birthday party for my aunt on Saturday and I was looking at my baby cousin. Instead of cooing at him, I just looked at him and said I’m really sorry about the earth.”

Right now, Chantelle is weighing her options.

“I understand that, by going into health, I could end up in a bigger shop with a bigger team and a larger salary, but also have a smaller role. And, maybe, work with people who are a little less invested because they only have that small role to play. Whereas in the environmental area or the arts, the salary might not be there, but I would have more skin in the game, so to speak.”

Chantelle thinks it’s going to be about trade-offs.

“On the one hand, I’m a typical millennial who is worried about student debt and who may never retire as a result of it. I think right now, my student loan is between $20 and $25 thousand. On the other hand, a huge reason I wanted to get into fundraising is because I want to feel like I’m doing something important and fulfilling with my time.”

“I think always putting your best foot forward and being on the ball is what’s going to make you a good fundraiser. And whatever it takes for you to do that, it’s something that you need to be able to give 100% of yourself.”

Chantelle is searching for an internship and finds the prospect scary—and exciting.

“I just think that any time you go through major changes in your life, it can be so uncomfortable,” she says. “Growing pains, right? It’s kind of like keeping my chin up during those growing pains and remembering that it’s going to be very worthwhile to get through it and the lessons I’ve learned through it are probably lessons I’ll keep with me my entire life.”

Epilogue: Chantelle found an internship with the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) working on planned giving. After her internship, she became the planned giving coordinator at Nature Conservancy Canada and is currently the coordinator of corporate partnerships.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.