By Kathleen Adamson, June 20, 2022

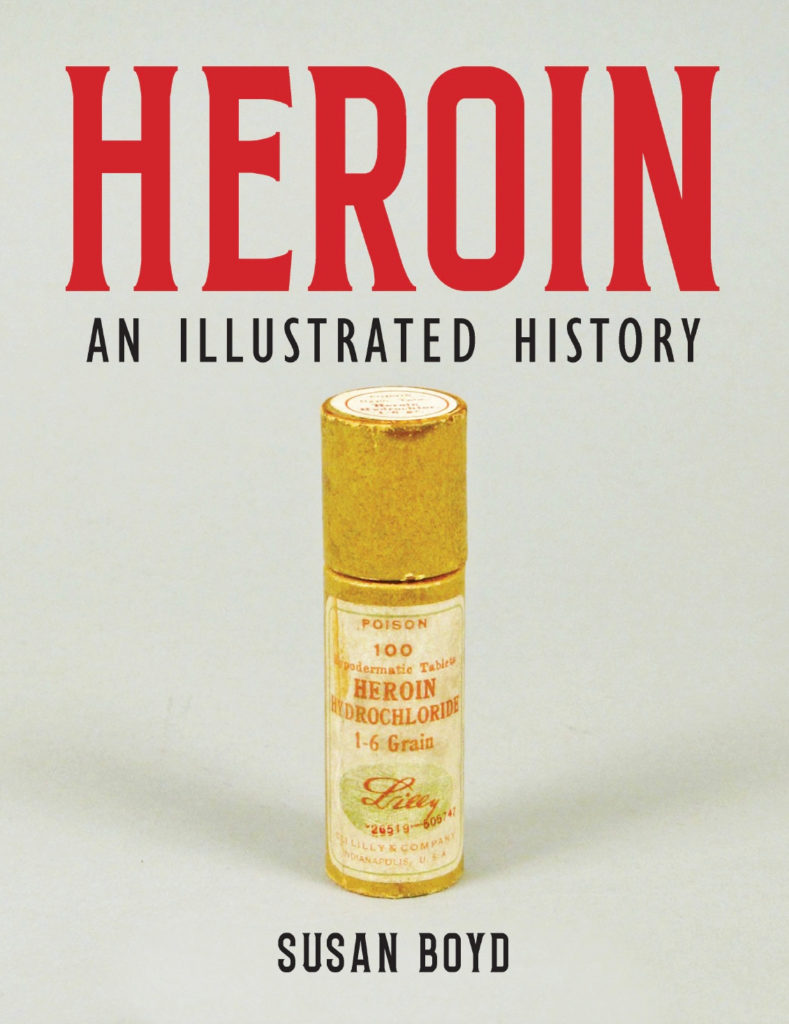

Heroin: An Illustrated History, Susan C. Boyd, Fernwood Publishing, May 15, 2022, 176 pp, $34.00

(June 20, 2022) Susan Boyd’s comprehensive and compassionate Illustrated History of Heroin is a welcome addition to the growing wave of scholarship on drug use, drug addiction, and the role of drugs in social culture.

An increasingly large number of Canadians know someone—or many people—who have suffered from opioid addiction or overdose. These already high numbers have been fueled by pandemic stress and isolation. Yet the use of opioids remains immensely stigmatized, despite the accepted—even glorified—uses of caffeine, alcohol, and cannabis. Heroin and other opioids were criminalized because they were thought to be harmful to society, and seeing the suffering of those addicted, the association seems obvious. But what came first—the suffering or the criminalization? Boyd addresses the book to this question, and the result is a riveting and eye-opening read.

The book begins in the late 19th century. Many readers will be familiar with the early uses of opium in medicine, but Boyd moves beyond the amusingly anachronistic advertisements to open many of the difficult folds in our history, like Residential schools, and the systematic mistreatment and internment of Asian people in the early 20th century, among others. There’s the story of Emily Murphy.

In the 1920s, Murphy was a journalist, and would eventually become the first female magistrate in the British Empire. A Canadian, she was a suffragist, temperance advocate, and a supporter of eugenics. Her temperance advocacy metastasized into a series of articles and stories sensationalizing drug use and developing a narrative in which virginal white women were corrupted with drugs (inevitably associated with sexual promiscuity) by Black men. Like the notorious 1971 book Go Ask Alice a work of fiction marketed as a true story about a teenage girl, who develops a drug addiction and at age 15 and runs away from home, these works contributed to an unrealistic, destructive, and ultimately stigmatizing portrayal of drug users. Throughout the the book, Boyd expertly untangles the relationship between sensationalist anti-drug propaganda, criminalization, and the suffering of marginalized peoples. Her dedication to harm reduction and anti-racism work is clear.

The last chapters cover developments in drug criminalization that will be within many readers’ living memory, but Boyd’s perspective is very fresh. As we have reported here previously, the COVID-19 pandemic and its two horsemen of isolation and lack of access to support services has thrown fuel on an already blazing fire.

In British Columbia, the provincial government has announced a plan to decriminalize the possession of small amounts of opioids, as part of a major effort to ease their opioid crisis. Boyd shows that these, and similar supportive programs, are much more effective in easing suffering than the aggressive criminalization of opioids. With colour photographs scattered throughout and an adept, authoritative narrative, Boyd’s book will appeal to readers of all kinds.

Also reviewed by Kathleen Adamson

Is America’s next civil war already in progress? March 14, 2022

Nora Loreto and her book Spin Doctors are here to tell us how we got here January 24, 2022

The Rebel Christ: Scriptural support for a radical Jesus November 26, 2021

What Comes from the Spirit: The exquisitely balanced voice of Richard Wagamese October 18, 2021

Jigging for Halibut with Tsinii: Its relatively still waters run deep September 24, 2021

Deaths of Despair: how the flaws in capitalism are fatal for America’s working class September 9, 2021

Ivan Coyote: Bringing stories of fierce love and community building August 30, 2021