Conversations with Dickens: A Fictional Dialogue Based on Biographical Facts by Paul Schlicke

Successful Philanthropy: How to Make a Life by What You Give by Jean Shafiroff (Author), Georgina Bloomberg (Introduction)

My Dinner with Dickens

By Katherine Verhagen Rodis (February 7, 2020)

Conversations with Dickens: A Fictional Dialogue Based on Biographical Facts, Paul Schlicke, Forward by Peter Ackroyd, Watkins, November 12, 2019, 118 pp, $16.95

Conversations with Dickens is a treat for anyone who has ever asked, “if I could have dinner with someone famous, alive or dead, who would it be?”

Part of a series that creates fictional conversations with prominent historical figures such as John F. Kennedy, Oscar Wilde and Casanova, it is a joy for the Dickens fan who would choose the prominent Victorian author as a dinner companion.

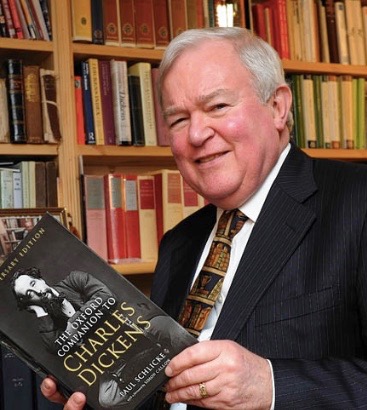

In the book, Dickens appears as a ghost having a fictional after-dinner chat with the author, renowned Dickensian scholar Paul Schlicke, when Dickens has been “seven weeks dead.” It starts off with the two sharing “a steaming bowl of punch.” Given Dickens himself loved a good ghost story when he was alive, he would likely approve of Schlicke’s fanciful characterization.

Informed by Peter Ackroyd another leading Dickens scholar, who wrote the forward, Conversations contains details about Dickens’ life that range from the noble to the salacious. From heated international copyright arguments with publishers to the dissolution of his marriage to his relationship with a young, beautiful “travelling companion” in his later years, Ghost-Dickens shares intimate details with Schlicke.

Ghost-Dickens proves to be every bit the energetic character in death as he was in life: gesticulating wildly, strutting about in an excitable manner as if he is crossing a stage or about to lead a grand waltz. He frequently interrupts his interviewer with emphatic phrases like “Oh lor no!” or “God bless my soul.”

Known as a “champion of the working-class,” Dickens was one of the few authors of his time to choose orphans and convicts as lead narrators or prominent figures in his novels (e.g.Oliver Twist) or to explicitly mock prevailing economic philosophy of his time (e.g. Utilitarianism and laissez-faire capitalism in Hard Times).

Ghost-Dickens tells Schlicke about his “firm conviction that every man and woman in this country should have the right to decent food, shelter and common comfort.”

He reveals that “little Oliver’s progress” is predetermined to “gravitate inexorably into a life of crime.” According to ghost-Dickens, the system “treats poor people worse than criminals.” Oliver falls into pickpocketing only because society’s law and paltry social relief systems abandoned him.

The author writes that Dickens “worked indefatigably to promote education for working-class children and adults” to help them gain opportunities that he had struggled so hard to find for himself. “Anything that can lift wretched children out of woeful ignorance is a big step in rescuing them from a life of crime,” says Dickens.

Schlicke provides an engaging and concise preface that charts Dickens’ rise to literary fame, from poverty to considerable wealth, and from public advocate for the working-class to—with increased fame and fortune—deepened engagement in charitable work,

“Dickens collaborated with [a] wealthy philanthropist [of the time] in establishing schools for the poor, urban housing schemes and Urania Cottage, a refuge for homeless women.”

During these cold winter months, the warmth and humanity of Dickens’ words will provide a welcome refuge from a man who claimed to place above all else “common bonds of love, generosity and selfless concern for one’s fellow creatures.”

(Katherine Verhagen Rodis is Senior Coordinator, Philanthropy and Prospect Research at Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital Foundation. She has a deep love of modern interpretations of Dickens’ work that excite the imagination. In order of descending importance, favourite adaptations include those made by: 1. South Park. Malcom McDowell narrates an abridged version of Great Expectations that includes the welcome addition of a maniacal machine powered by Estelle’s ex-boyfriends’ tears and Miss Havisham’s robot-monkey minions. 2. The Muppet Christmas Carol Dr. Bunsen Honeydew and his assistant Beaker form my favourite team of beleaguered major gift officers. 3. Doctor Who. Eccleston’s Doctor Rose Tyler and Charles Dickens himself face off against menacing zombies from beyond the stars.)

From Bleak House to Manhattan Society

By Gail Picco (February 7, 2020)

Successful Philanthropy: How to Make a Life by What You Give, Jean Shafiroff (Author), Georgina Bloomberg (Introduction), Hatherleigh Press, March 16, 2016, 288 pp., $18.00

As Katherine Verhagen Rodis notes in her review of Conversations with Dickens: A Fictional Dialogue Based on Biographical Facts, Dickens was not only an advocate for the poor, but as he became more wealthy from his book publishing, he became a philanthropist. And the role of the philanthropist, how they operate, who they are and what they get out of giving is justly being debated in wider society in these surly times. “

One of my very favourites scenes in The Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens is the one where two men visit the offices of Ebenezer Scrooge on Christmas Eve, the 7th anniversary of Jacob Marley’s death. They are taking up a collection for the poor. And it’s remarkable how little the essential nature of the fundraising pitch has changed,

At this festive season of the year, Mr. Scrooge,” said the gentlemen, taking up a pen, “it is more than usually desirable that we should make some slight provision for the Poor and destitute, who suffer greatly at the present time. Many thousands are in want of common necessaries; hundreds of thousands are in want of common comforts, sir.”

“Are there no prisons” asked Scrooge … And the Union workhouses?”…

“Under the impression that they scarcely furnish Christian cheer of mind or body to the multitude,” returned the gentleman, “a few of us are endeavouring to raise a fund to buy the Poor some meat and drink, and means of warmth. We choose this time, because it is a time, above all others, when Want is keenly felt, and Abundance rejoices. What shall I put you down for?”

“Nothing!” Scrooge replied.

“You wish to be anonymous?” “

I wish to be left alone,” said Scrooge.

Successful Philanthropy: How to Make a Life by What You Give by Jean Shafiroff with an introduction by Georgina Bloomberg, which was published almost four years ago, but which I felt could be juxtaposed against the Dickensian scene painted by Katherine Verhagen Rodis’ review. The book gives us an insight into a segment of philanthropists that is not necessarily the newly-minted trope of the ultra-wealthy business man wading in to fix the problems that rampant capitalism has created. They are more—how shall I say this without offense—they are the ladies who lunch or, as the business media calls them—socialites, socialites and philanthropists. And they control hundreds of millions of dollars in philanthropic spending.

Two of them have contributed to this book. Jean Shafiroff is the author and Georgina Bloomberg, daughter of billionaire and presidential candidate Michael Bloomberg provided the forward. They have known each other since university. One grew up extremely wealthy. The other did not.

According to the New York Times, “Mrs. Shafiroff, 62, estimates that she and her husband, Martin D. Shafiroff, a former Lehman Brothers managing director, contribute nearly $1 million every year to charities, and solicit an additional $800,000 from their wealthy peers. As a measure of her social standing, she sits on the board of seven well-connected charities, including the French Heritage Society.”

Georgina Bloomberg is a professional equestrian, the owner of the equestrian team New York Empire (and a philanthropist),” according to Town and Country magazine. An outdoor gallery space at the new Whitney Museum of American Art named is named after Bloomberg’s six-year-old son Jasper Bloomberg.

Unlike Bloomberg, “Shafiroff exemplifies a new breed of hands-on philanthropist, one who isn’t necessarily born with the right family name, or introduced through debutante balls, or nurtured through the ranks of junior benefit committees,” said the New York Times. “Instead, she is what her husband calls a working socialite, who regards the philanthropy circuit as a profession and is a master of promoting her own image alongside the charities she supports.”

If you’d like to get inside the head of the women who control the millions, Successful Philanthropy is an informative read. The book is written to help prospective philanthropists get a handle on their giving. And Shafiroff suggests great questions—do you think you can add value? Are you comfortable with the people involved? Does the charity do its job? Do you think the charity has a strong board?

At the same time, she lays down a few rules of the road for philanthropists. You can’t have conflict of interests, she advises.

“The rules of conduct for you are the same as they are for someone who works full- or part-time as a paid employee of the organization. Do not presume to know how to do things better than others. If you have a suggestion, offer it politely … Be sure to treat other volunteers well.” Treat those served by the charity with “kindness, dignity and respect … all potential donors must be treated with respect.”

After directing campaigns where campaign gossip rules, one of my faves is “Anonymous donors are those who do not want their gifts discussed and who wish to keep their gifts a private matter.”

For the many working in fundraising who wonder what donors are thinking, how to best appeal to them, imagine how they want to be treated, this is a small book and an easy read.

Successful Philanthropy answers those questions in a fun and accessible way from someone who hauls herself out, dressed to the nines, four nights a week during the fall gala season. I, for one, am listening.

In the New York Times profile of Jean Shafiroff, which is a fun sidebar read to this book, her husband Martin D. Shafiroff“admiringly recounted his wife’s moxie in soliciting donations from other wealthy New Yorkers. “I’ve seen calls where people were screaming at her,” he said. “Screaming: ‘How dare you call? How dare you ask for a gift?’”

The Times goes on to say that, “while husband and wife may spin it differently, there is no question that Mrs. Shafiroff is a fearsomely effective fund-raiser. She has ramrod posture and diction to match, cultivations that emphasize a steely conversational focus on herself and her causes.”

A fun dinner match-up then? How about Jean Shafiroff and Ebenezer Scrooge? I know who I’d be rooting for.

(Gail Picco is a fundraiser, charity strategist, author, editor and writer.)