A story about the essential connection of culture and heritage to wellbeing and self-esteem

Reviewed by Sharon Broughton (First published August 15, 2019)

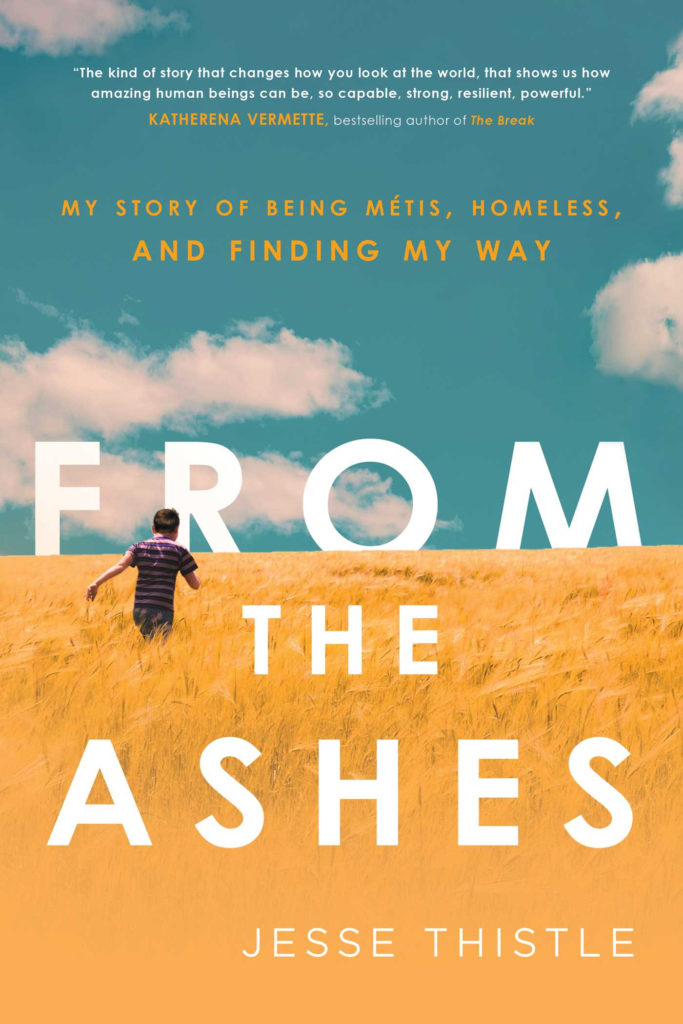

From the Ashes: My Story of being Metis, Homeless and Finding My Way by Jesse Thistle, Simon & Shuster, August 6, 2019, 368 pp., $19.80

From the Ashes is the compelling first-person memoir of Jesse Thistle’s journey, through the darkest of times to reconciliation and renewal. It is hard, but essential, reading. It tugged at my heart and spirit. I couldn’t put it down yet, at times, I couldn’t keep reading.

This is a Canadian story. It is for those looking to better understand the lived experience of Indigenous peoples and the depth of the loss of relationships with the land, family, elders and community. For me, as a non-Indigenous person, it is a story that supports the path of learning and reconciliation.

It took 37 years, and more hardships than most will ever experience, for Jesse Thistle to be reunited with his Metis-Cree heritage, culture, language and traditions, a connection lost when he was three years old.

Surrendering to the memories of the smell of his grandmother’s cooking and the sound of his grandfather’s music, Jesse falls to his knees on the land where his grandmother Kokum Nancy’s cabin had been. Saskatchewan remembered him, the land whispering his welcome home.

His haunting words “I remembered them. I remembered my mother’s people. I remembered who I was” convey both the immeasurable sorrow of loss, as well as the deep joy of rediscovery.

Told chronologically through sharply-focused vignettes of incidents in childhood, adolescence and adulthood, and interspersed with Jesse’s original poetry, From the Ashes is a page-turner. Through the lens and voice of his earliest childhood memories to the once homeless, drug-addicted man he became to the now clean and sober Jesse of today—a PhD student, national representative on Indigenous homelessness, a Trudeau and a Vanier scholar—his story is revealed.

We first meet Jesse as he picks Saskatoon berries in the bush by the railway tracks with his maternal grandmother, a proud Michif woman in Saskatchewan, and we follow him as he is abandoned, along with his two older brothers, by both of his parents when the three boys were all less than six years old. From the poverty and hunger he experienced while in his father’s care to the grim struggles living at the hand of children’s services to landing halfway across the country at the Brampton, Ontario home of his paternal grandparents—who offered as much stability and safety as they could—the trajectory of his early life left a deep mark on Jesse. And through it all, his Indigenous heritage was denied, silenced and lost.

By his early 20s, after faltering in school and haunted by the disintegration of his family and parents—whose own struggles with violence and trauma meant they were not able to care for him—his life slid out of control into a cyclical haze of drug use, petty crime and homelessness.

“Hard” is a worthy descriptor of this book: the story is about hard lessons, hard times, how hard it is to let go, to give up, as well as how hard it is to believe how far a person and family can be stretched past the breaking point and still recover.

The darkest times are captured with the spare and haunting words of his poems. In reading “Windigo,” I experienced how his survival was truly against all odds:

“…

starvation sets in

breath freezes

in january’s wind

lost and alone,

wandering.

I swill back the pain; it burns and belches

rage and despair

leaving only a windigo

who cannibalizes himself.”

Jesse’s redemption begins when, on a second time through a treatment program in Ottawa, he began to study and learn, for the first time, about his family’s real history. As he recovers from addiction, he processes the unimaginable pain of intergenerational trauma and the repeated history of abandonment. Finding his own reasons why everything in his life unfolded as it did, he begins the journey back to who he is. With exceptional focus, determination and strength of character, Jesse develops a new future for himself that includes finding friendship, love and a life partner, as well as a passion and vocation.

This book is a story of turning points, of resilience and hope, of the kindness of strangers, of how important a leg up at the right time, in the right way, can be, and of the essential connection of culture and heritage to wellbeing and self-esteem.

In his final poem My Soul Is Still Homeless, we hear his struggle to fully grasp how far he has come and where he is today:

“….

At night,

In between slumber and consciousness

I sleepwalk

My soul not yet aware

That my wanderings are over

And I have a home.”

When he learns who he really is: “You’re Cree and road allowance Michif, Jesse. You come from a long line of Chiefs, political leaders and resistance fighters,” I felt like cheering him on, wishing he and his wife the best for a future where they create a new story for their families, honouring their reclaimed history and culture.

I am thankful to Jesse Thistle for this offering of himself, for shining a light on the profound and damaging effects colonization has had on Indigenous peoples, and for sharing the rays of hope his focus brings.

On a personal note, I have had the unique privilege through my work of having visited Northern Saskatchewan and several First Nations communities in support of projects to revitalize Indigenous languages. In recognition of the importance for young people to see, hear, learn and experience their culture, language and heritage with pride, this work has focused on children’s books. I know that today, students are learning and speaking Michif and Cree, something Jesse did not have the opportunity to do as a child. I find myself imagining a future Michif children’s book to capture a link to Jesse Thistle’s story.

(Sharon Broughton, M.Ed., is currently the CEO of Prince’s Trust Canada, a national charity focused on youth employability, veteran entrepreneurship and Indigenous language revitalization.)