By Gail Picco (July 26, 2021)

Likeness: Fathers, sons, a portrait, David Macfarlane, Doubleday Canada, May 18, 2021, 240 pp., $29.95

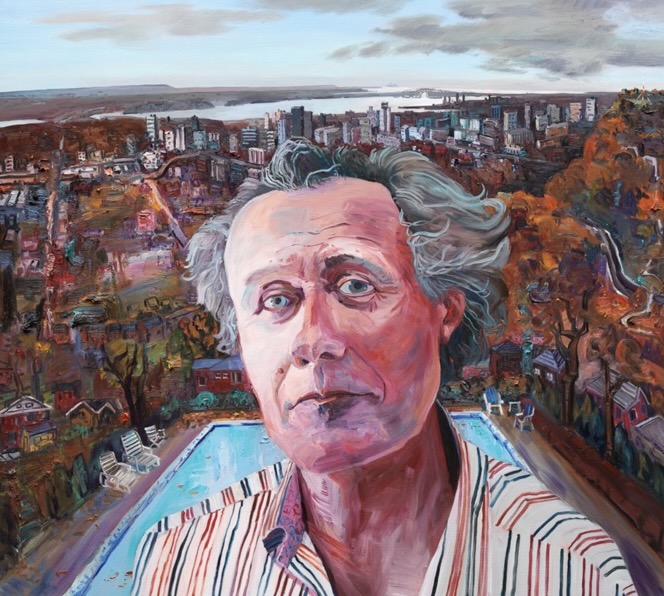

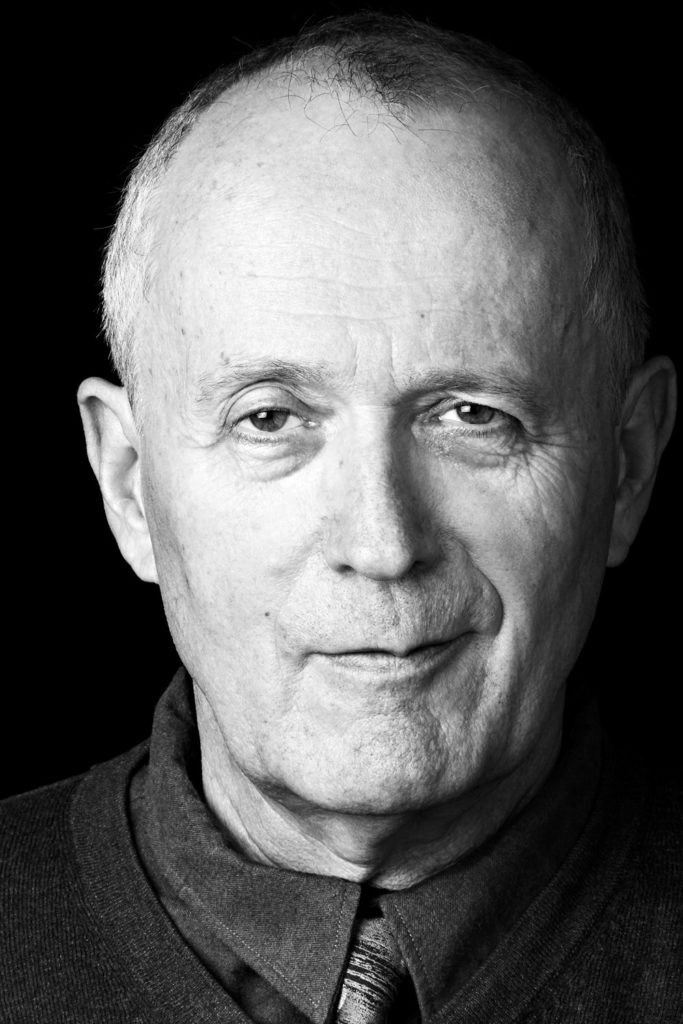

In Likeness, an achingly sad and sometimes hilarious memoir, David Macfarlane uses a portrait of himself created by preeminent Canadian painter John Hartman as a vehicle to access his memory. The painting is part of a project by Hartman’s Many Lives Mark This Place—depicting well-known Canadian writers against the backdrop of the geographical space that inspires them.

Seeing the painting at the exhibit’s opening, Macfarlane told the gallery owner Nicholas Metivier the only thing a card-carrying magazine writer could say as he stared gobsmacked at the 5 x 5 ½ foot painting of his own face against the backdrop of Hamilton, Ontario.

“I think I can write about that.”

Within days, professional art installers had put the painting up in the little-used living room of Macfarlane’s house, a 100-year Victorian home at College and Spadina. Considering the proportions the sparsely-used living room, visiting the painting was an immersive experience for Macfarlane, offering him both an oasis and a no-fly acid trip. As he stares at each square inch of paint that in and of themselves resemble nothing in particular, memories offer up as much or more than a Proustian madeleine—feelings, vignettes, conversations, entire stories from his past come rushing out. (Macfarlane was fond of his LSD back in the day.)

“The closer you get to the painting, the harder it becomes to guess what follows what. You leave the narrative of a portrait, and get to someplace new.”

The narrative thread that allows Macfarlane to skillfully fly around to any part of his past and come home to roost in the brutally sad reality is that David Macfarlane’s son Blakely Macfarlane is dangerously ill after being diagnosed with leukemia in 2014 and has moved back home into an apartment Macfarlane and his wife had installed in their home years before.

“This was a worrisome period—by which I mean, there was a lot of worrying about Blake going on. Not always, of course. Not constantly. But the future you can see me looking toward in Hartman’s painting is what I mostly wondered about, and that future is where I am now. What I didn’t know then, I know, and the interim is what the painting is about—at least, that’s what it has come to be about for me. That’s what I see.”

The progression of Blake’s illness allows the reader to keep time in the real world, giving Macfarlane free rein to describe—in his taut, yet descriptive bon mot prose—how it felt to be part of a generation that, at least for a time, felt like the world was made for them, and what being able to feel that means to him now.

When Blake was in hospital Macfarlane read him the work inspired by the painting, thinking it would be a good way to pass the time. Blakely was a film editor, DJ, music enthusiast and chronicler with an excellent eye for narrative.

“Blake felt as most sons do at some point in their relationship with their fathers: obliged to state the obvious … Just because something could be recalled didn’t mean it was worth a detailed description.”

Right.

But Macfarlane confesses,

“What I didn’t tell Blake was that entering the painting’s imaginative space was an opportunity for me to enter another world for a while—a world that was comforting because it wasn’t the present. So I’d sit in the living room. So I’d look at the painting. I’d remember things, which was a change from worrying about things.”

There were moments in this book when I just had to put it down and weep.

“One night the pain wouldn’t stop. I won’t try to pretend I have any idea what it felt like. But I will tell you what being the parent of a child in pain like that felt like: it felt like my nerves were exploding. I remember standing in front of him and crying—full-throated sobbing—because there was nothing we could do to help.”

But there are moments of joy and hilarity, our ability to appreciate them honed by our own cares and tragedies.

After The Danger Tree was published in 1991 to international acclaim, hearing more about his father and delight in stories of his mother’s cheeky, hit-the-nail-on-the-head humour is pleasant.

“I think it’s fair to say that the broad outline of Blake’s view of his future would be something like this: if civilization was going to survive environmental, economic, and democratic cataclysm (not an outcome on which he’d be willing to bet) everything was going to be different. Very different. As I pointed out to my mother, if your general context is the collapse theory, career planning can be complicated. Certainly, more complicated than her generation, or mine, had known career planning to be. “Sometimes,” she’d say at a conversational impasse such as this, “I don’t think I can get out of this world fast enough.”

One of the most remarkable things about the book is that David Macfarlane writes about Hartman’s painting without ever actually showing us what it looks like. There’s no picture of the painting in the book. But by going to manylives.art, the reader can see Hartman’s work and follow along with Macfarlane’s descriptions. (There is a small rectangle there. It’s to the right of my right eye, Macfarlane writes on page one.)

A beautiful and sometimes heart wrenching read, Likeness ultimately redeems us with the knowledge of what it’s like to love and be loved.

(Gail Picco is the editor in chief of The Charity Report.)

More reviews by Gail Picco

Sylvia Olsen Unravelling Canada: Pulling at the stitches of Canadian history June 22, 2021

A Girl Called Echo: A Resounding Messenger of Métis History May 10, 2021

David Love: Thoughts of an Environmental Fundraiser April 30, 2021

What Bears Teach Us: The push and pull of co-existence December 8, 2020

Begin Again by Eddie Glaude: James Baldwin as a Man for our Time November 30, 2020

She Proclaims: The necessity of women persistently proclaiming October 20, 2020

The reputation of philanthropy: A history of the facts September 18, 2020

Juneteenth: ‘The most keenly awaited novel of the 20th century’ June 19, 2020