Conversations with Buddha: A Fictional Dialogue Based on Biographical Facts, Joan Duncan Oliver with forward by Annie Lennox

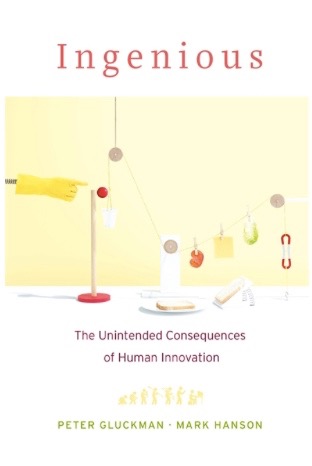

Ingenious: The Unintended Cost of Human Innovation, Peter Gluckman and Mark Hanson

Imagined conversations on suffering, impermanence, and karma

by Lucy White (February 14, 2020)

Conversations with Buddha: A Fictional Dialogue Based on Biographical, Joan Duncan Oliver with forward by Annie Lennox, Watkins Publishing, Reprint Edition, November 12, 2019, 128 pp., $16.95

Are we nearing peak mindfulness yet?

I can’t imagine that mindfulness and meditation have ever been more popular, yet despite the rebranding of Buddhist practices as mindfulness, Buddhism itself isn’t really very well understood.

Joan Duncan Oliver’s new book Conversations with Buddha: A Fictional Dialogue Based on Biographical Facts is a fresh attempt to demonstrate that Buddha’s humanity still can speak to modern westerners who, like the Buddha, have it all – love, money, status, and privilege. But the Buddha set his pampered life aside to search for something deeper and more enduring. His teachings explain how we can do the same despite our stressful lives.

I’ve been studying and practising meditation off and on for more than 20-years (Full disclosure: more off than on!) and, even so, it has changed my life. My current work as a consultant and, before that, as an association executive director is hectic and demanding. It’s easy to work too many hours, bring work home, and drive myself to distraction thereby causing the very suffering I want to avoid. Meditation and mindfulness help me deal with emotions and cravings (time to panic, the report is due tomorrow!) and reduce needless suffering.

I was intrigued by Conversations with Buddha. Could this little book, just 110 pages, get me a few steps closer to mindfulness? Make the Buddha’s teachings more accessible?

The book is in two parts: a breezy retelling of Buddha’s life followed by an imagined conversation between Oliver and the Buddha.

Buddha began his life as Siddhartha, a wealthy and powerful prince. But Siddhartha has a mid-life crisis and decides to take up life as a wandering monk. Just as he is about to leave his palace, he has his first run in with the voice of temptation, Mara – the “Evil One.” If Siddhartha would just forget this silly renunciation idea and turn back to the palace, in seven days he would be a universal monarch, Mara promises.

Siddhartha brushes him aside. Big mistake, Mara counters.

Once Buddha reaches enlightenment, he seeks out his former followers to tell them about his discoveries. He meets an “old pal” on the way.

“Wow, you look terrific—so serene,” the monk says. “Who’s your teacher?” When the Buddha replies that he has been working alone, the Monk mutters, “Whatever.”

The second part of the book contains conversations organized around thirteen themes: suffering, impermanence, non-self, karma, and so on. It opens with Buddha’s discovery of the Four Noble Truths notably that life is suffering but there is relief from suffering through following the Noble Eightfold Path. And, this is where the going gets difficult.

The summaries that precede each section are excellent. Introducing mindfulness, for example, Oliver writes,

Practically speaking, the Buddha’s teachings are about training the mind. A well-trained mind is calm, clear and aware. It isn’t pulled this way and that by desires, disturbances or delusion. Mindfulness—attentiveness—makes every experience richer and more rewarding. When you’re paying attention, you live in the here and now, not in the past or future. Mediation sharpens your focus, giving you insight into your motivations and behaviour. It keeps your eyes on the ultimate prize—liberation.”

And the Buddhist concept of suffering is explained. It’s as realistic, not pessimistic. Life is difficult and there is suffering, such as physical pain, but also mental anguish. When we want something and not get it or get what you don’t want is suffering. The aim is to acknowledge this and realize that it will pass without holding on so tightly we create more suffering for ourselves.

On the other hand, the Buddha’s explanations can be dense and complex.

Even a world expert such as Oliver finds it difficult to balance the Buddha’s own words and still convey these teachings simply and clearly. In speaking of rebirth and reincarnation, the Buddha starts describing the 10,000 world-systems, 31 planes of existence and 16 realms of Devas. In describing the experience of non-self, Buddha says,

“The meaning of non-self isn’t that nothing exists, or that what you perceive with your senses isn’t real. Conditions come together, resulting in the phenomena we experience. These phenomena exist—they just don’t exist independently of the conditions that caused them.”

I found myself glazing over.

But here’s the interesting thing. I keep going back to this little book. Now that I’ve read it through once, I’m enjoying dipping in and reading short passages, mulling them over through the day. I’m meditating more frequently and, yes, I feel a little calmer and more present to my life despite the fact that I haven’t finished that dang report I’m working on.

(Lucy White is currently the interim executive director at Editors/Réviseurs Canada and is a principal at The Osborne Group in Toronto.)

When innovation bites back

by Gail Picco (February 14, 2020)

Ingenious: The Unintended Cost of Human Innovation, Peter Gluckman and Mark Hanson, Harvard University Press, October 15, 2019, 336 pp., $28.06

How did we get here?

The planet is on fire. Democracy is crumbling. Misinformation is intentionally distributed by the world’s largest technology companies (and others) on a daily basis. The gap between the rich and poor grows unimpeded.

In Ingenious: The Unintended Cost of Human Innovation, authors Peter Gluckman and Mark Hanson talk about what happens when we innovate in a way that results the innovation “biting back.”

It is a part of a cohort of books written by significant writers and academics assessing where we sit as humans in evolutionary terms and encouraging us to become more intentional in our process of innovation.

Sir Peter Gluckman is Director of the Centre for Science in Policy, Diplomacy and Society at the University of Auckland and Chief Scientific Officer for the Singapore Institute for Clinical Sciences and president of the International Network for Government Science Advice. Mark Hanson is British Heart Foundation Professor and Director of the Institute of Developmental Sciences at the University of Southampton.

Ingenious contains rich and accessible detail that helps explain how a species evolves in relation to external pressures and its generic expression.

Biological evolution, the authors write, is constrained to some extent by genetic makeup. Cultural revolution, by contrast, can happen quickly, without constraint, among peers and unrelated individuals.

Environments can vary over the course of many years,” the authors write. “They can also fluctuate between years and seasons and even over days. This means that however well suited a species is to an environment, it must be able to cope with changes in that environment …Today, in response to climate change, many flowers are opening earlier in the season and birds are changing their nesting habits.”

What is new today is the “scale and seek of the environmental changes and the effects we are producing on other species.”

And some of the technological innovations have raced along so quickly we’re coming up a bit dazed on the flip side.

- There’s the development of antibiotics vs rising rates of autoimmune diseases and antibiotic-resistant bacteria, for example.

- Internet and social media vs mental health and the disintegration of truth and the social fabric

- Industrialization vs the massive increase in CO2 emissions.

The asymmetry of our approach to innovation is a testament to how a lack of imagination (or willfully ignoring the consequences) has resulted in the anticipation of the downside of technological advancement, and therefore no action for mitigation.

But, given it sadly the lack of anticipation of downsides seems to be part of human nature. Advertising for alcohol and increased government revenue from alcohol sales bears does not account for the comparative social programs needed for alcoholics. Electronics, toys and other do-dads that are sold in hard, sharp, industrial strength plastics to go to landfill once the package is open. Beautifully packaged cosmetics are landfill once the eye shadow is gone. It is as if products and their impact disappear once they are out of the makers’ sight. One might think that lack of foresight or anticipation is an evolutionary gremlin in the human psyche.

And given the charity sector is looking to technology such as social media, virtual reality and artificial intelligence to solve, fundraising and other issues, it is like worth some time to consider the whole innovation ball of wax.

Ultimately, and unsurprisingly, the authors suggest we face some fundamental questions.

Will we wait passively to see where technology takes us? Or do we want to be more deliberate in the controls we apply to it—and, if so, how do we do this individually and collectively? How do we get the best from technology and restrict its worst efforts? What are the respective responsibilities of individuals, elected governments, international nongovernmental organizations, and global corporations?”

Virtual reality and artificial intelligence are speeding towards us, as is the momentum for whatever falls under the broadening rubric of innovation. It might be time to expand the innovation discussion to include impact, adaptation and mitigation. Peter Gluckman and Mark Hanson suggest it’s all hands on deck.

(Gail Picco is a fundraiser, charity strategist, author, writer and editor.)