By Gail Picco, December 2, 2020

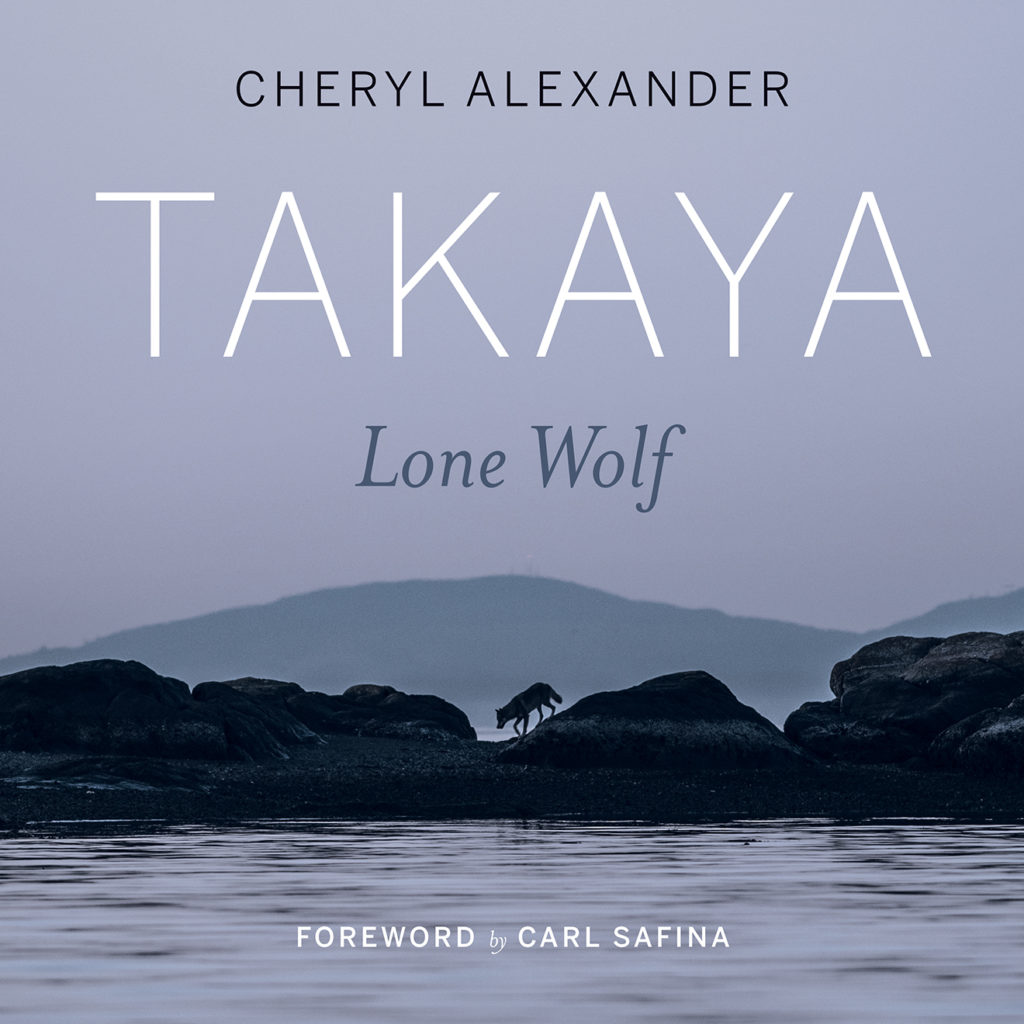

Takaya: Lone Wolf, Cheryl Alexander, foreword Carl Safina, Rocky Mountain Books, September 29, 2020, 192 pp., $29.70

Takaya is the Coast Salish First Nations people’s word for wolf.

“Takaya’s life was very odd for a wolf,” writes Carl Safina in his forward to Takaya: Lone Wolf. “Wolves are very social. They usually live in families, just as we humans do. Takaya came, alone, to a small island without food or reliable fresh water. Yet this unusual, mysterious, different wolf found his way to survive, for years.”

The small island Takaya made his way to, from heaven knows where, was a small archipelago of islands at the southern entrance of the Salish Sea off the coast of Vancouver Island, which became, more or less, connected during low tide.

The islands were boating distance from where accomplished conservation photographer Cheryl Alexander lived with her family. There had been some reported sightings of a lone wolf, one in May 2012 on the Sannich peninsula, a suburb of Victoria. Eventually, the wolf had made its way to the uninhabited archipelago. Alexander explored the small islands herself in hope of a sighting and on Mother’s Day 2014, while hiking with her husband, she saw the wolf for the first time, and says that she was profoundly affected. At the time, she had been focused on learning about and photographing the many whales off the west coast of British Columbia. But, she says,

“…it was a wolf that captured my focus—and my heart. Six years later, I have come to know so much more about wolves than I ever imagined … I wanted to know where he came from, what he was living on and why he stayed on these islands.”

Takaya’s habitat—Discovery Island,Chatham Islands and Trial Islands—is on the traditional lands of the Songhees Nation, descendents of the Lekwungan, “Indigenous people who have lived in the area for over 10,000 years.” Alexander said she sought and received permission from the Songhees chief and council to be on their lands to photograph and film Takaya.

For the Songhees people, the wolf is integrally linked to the perspective of the land. They considered the arrival of Takaya in 2012, just before the death a beloved chief, Robert Sam, an auspicious one.

For the next six years, Alexander became an accomplished tracker, boatwomen, and wolf whisperer as she followed Takaya around his territory, getting to know his habits and rhythms, eventually developing a companionship with Takaya, until the six year idyll came to a sadly predictable conclusion.

This mid-sized coffee-table paperback is filled with glorious photos of Takaya, his habitat and the magnificent ocean setting. Alexander’s rich talent as a conservation photographer is revealed on every page. Takaya is beautiful in every shot. She theorizes that the omega-3 oils in his mostly marine diet (lots of seal meat) has made his coat lustrous and full, so much so that some believed he was a ‘Hollywood wolf,” an animal who had done his time in the movie business and been dropped off at the island to ‘retire.’

In his forward, Carl Safina talks about how “people detest wolves with a hatred so deep it feels racial. Such people have never seen a wolf. They are expressing fear.”

Yet, he goes onto say, that all dogs are descendants of wolves. Wolves live in pack families and we live in pack families.

“That’s why dogs instinctively know how to fit into a family … In no other animal does the mere movement of a body part affect our emotions like a dog’s wagging tail. We react instinctively to that tail just as we react instinctively to a human smile.”

Alexander made an acclaimed film about Takaya that aired on BBC and CBC and has become the documenter of his mysterious life, inviting us to consider our own lives, and our spiritual and real-life relationship with our animal cousins, and the irreplaceable gifts of the natural world.

Alexander recounts the experience of Doug, the gentlemen in the Sannich peninsula who saw Takaya in 2012. Seven years later, as she spoke to him, she said it was clear the encounter with Takaya had profoundly affected him.

“Doug had been sitting in his RV on his sister’s rural property when he saw movement out of the corner of his eye … Doug realized that it was a wolf standing no more than 10 feet away. Doug locked gazes with the wolf—a peaceful encounter that changed his life utterly.”

Doug explained he’d been going through a rough time and his marriage was ending, but “somehow, gazing into the eyes of the wolf changed things for him. He saw this lone wolf getting on with his life, and thought that if the wolf could survive alone, then so could he.”

To commemorate the impact of gazing into the wolf’s eyes, Doug had gotten the words “lone wolf” tattooed on his arms, from his wrist to his elbow, one word per forearm.

This book is beautiful, inside and out.

Also reviewed by Gail Picco

Begin Again by Eddie Glaude: James Baldwin as a Man for our Time November 30, 2020

She Proclaims: The necessity of women persistently proclaiming October 22, 2020

The reputation of philanthropy: A history of the facts September 18, 2020

Blowout: A tale of how the oil and gas industry took its seat at the head table of democracy, November 5, 2019