By Kathleen Adamson (May 23, 2021)

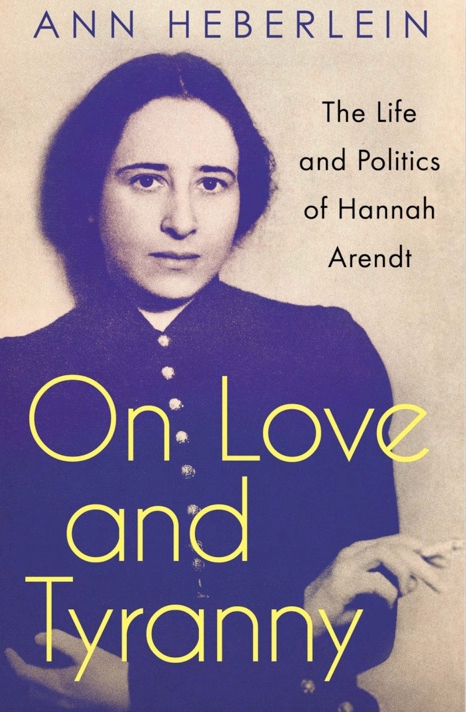

On Love and Tyranny: The Life and Politics of Hannah Arendt, written by Ann Heberlein, translated by Alice Menzies, House of Anansi, January 5, 2021, 272 pp., $24.70

Anne Heberlein’s new biography of Hannah Arendt sparkles with energy and clarity.

Hannah Arendt’s brilliance as a writer and political thinker has long been overshadowed by the controversial elements of her career. But with lively and personal style, Heberlein places each of Arendt’s major works in a biographical context that makes its relevance clear.

Some of Arendt’s ideas, like the ‘banality of evil’, which she developed in her writing about the trial of Adolph Eichmann, continue to circulate influentially. During Donald Trump’s presidency, her essays Lying in Politics and Truth and Politics resurfaced briefly, as thinkers returned to these works to try and process the relentless onslaught of lies.

Her extensive body of written work includes The Origins of Totalitarianism, On Revolution, Men in Dark Times, and The Life of the Mind, all of which are remarkable for their rigour and thoroughness. Like the best philosophers, she unfolds her ideas with the care and precision. Arendt, however, was also unpopular for some of her actions and opinions, including her friendship with Martin Heidegger, the German continental philosopher, who was once best known for his seminal work Being and Time, but is now notorious for his support of Nazism and Hitler before and during the Second World War, a position that was confirmed further when previously unread Heidegger notebooks were discovered.

After she publicly reconciled with Heidegger 1950, Hannah Arendt said she ‘forgave’ his anti-Semitic words and acts. In the wake of her forgiveness, many people called her anti-Semitic and said it was not her place to forgive him. But Arendt stuck resolutely to her guns, even when friends begged her to recant, and she still faces the Heidegger backlash today. The question of forgiveness is dealt with, beautifully, in the final chapters of Heberlein’s book.

The genius of Heberlein’s biography is its integration of Arendt’s personal life with her intellectual body of work. With a deft writing style that makes the book a joy for the reader, Heberlein describes Arendt in relation to her wide social circle and proximity to history. Her friends included many important European and American intellectuals of the time, and she corresponded widely with them. One of her close friends, Walter Benjamin, committed suicide during the Second World War, but his works, including The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, has continued to influence art and art history since it was published in 1936.

Hannah Arendt was no cold, indifferent scholar. Heberlein quotes her letter to close friend, the author Mary McCarthy, “I always knew, even as a kid, that I can only truly exist in love. And that is why I was so frightened that I might simply get lost. And so, I made myself independent. And about the love of others who branded me as cold-hearted, I always thought: if only you knew how dangerous love would be for me.”

Arendt knew that she contained as much passion as intellect, and worked hard to see things as they were, with the successes and failures that a brilliant and flawed person might have. In her letters, which are liberally and thoughtfully cited by Heberlein, she describes adjusting her ‘scathing’ opinions on the couple with whom she is living as she gets to know them better. No armchair intellectual, in addition to her long and prolific career as a writer and professor, she worked for Agriculture et Artisanat, preparing Jewish youth for emigration to what was then known as Mandatory Palestine. She also worked with the nonprofit Youth Aliyah to relocate child refugees displaced by Nazism. Later, she was imprisoned in an internment camp, from which she eventually escaped on foot.

Arendt’s fascinating life is served well here.

So many of the strange contradictions Why did Arendt so famously defend and even ‘forgive’ Martin Heidegger? Because he was her friend and she cared about him. Why did she push back so strongly in her own defense, when she faced accusations of racism and anti-Semitism? Because she was an intelligent, stubborn person with a great deal of confidence in her own opinions and the value of her lived experience. Why did she think she was able to ‘forgive’ any Nazis at all? Because she felt her experiences as a war refugee and internment camp prisoner gave her the authority. Why did she speak out in favour of prescribed gender roles between men and women, reject the label of feminist, even as she struggled to accept her own open marriage, which was an ethical stance against patriarchy and women’s oppression? Because, as a woman, she had succeeded in her own right and unconsciously assumed—as we all do to some extent—that anyone else might be able to do the same.

But the real beauty of Heberlein’s book is that it looks directly at the contradictions in Arendt’s work and personal life and integrates them, using her humanity and her personality as a guide.

(Kathleen Adamson is a musician, composer, academic, and community activist based in Montreal, Canada.)

Other reviews by Kathleen Adamson

Benjamin Miller: Very rarely does an author take political theory and interpret it with such relevance and clarity May 13, 2021